The Royal Society for the Blind (RSB) fears SA printers may lose access to its braille translation and embossing services following the federal government dropping funding for its Alternate Print Services.

The government has slashed the number of providers it will back in Print Disability Services from four to two, with organisations VisAbility and Vision Australia to share a total package of $5.7m from 2018-2021. According to RSB, the cuts will mean SA will no longer have a local provider, meaning individuals will have to seek braille and other alternate text interstate.

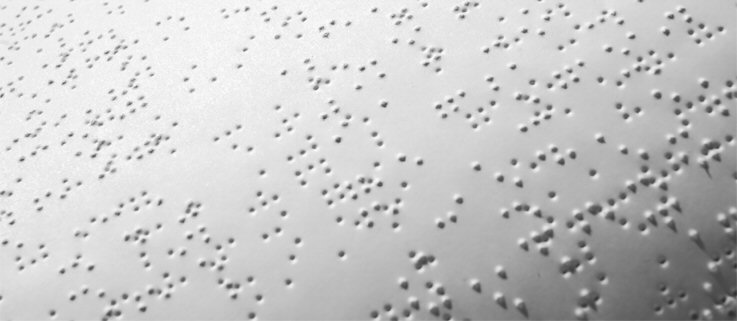

Funding under the scheme supports organisations to produce print material in large font or braille in addition to digital forms such as eText and audio, for people with disabilities such as visual impairment, deafness or a physical or learning disability.

Darrin Johnson, executive marketing manager at RSB, looks after its print services. He says, “We produce all of our own print material. We have a braille embosser and we work with printers locally, we do work for them if they want braille printed on business cards or labels, for example. It is done under a commercial model, but we need to have a full time braille translator and a printing fee will not cover their wages. We need to have funding to back it, and we may lose that service.

“The cuts are already in effect, they came in July 1. We are working with the governments to stop cuts to our services and we will be running on donation money for a few more months but we may have to stop if we do not get the funding. It is a bit of a dilemma for our donors, it is a difficult thing to asking for money for when there is federal funding in place for disability print services.

“In the Northern Territory, there also were no other services available up there anyway but in South Australia we have a large population of people with disability who now cannot access the service locally. The two organisations they are backing do not have branches in this state.

[Related: Federal govt cuts braille print funding]

“We may consider scaling back, we might get the stage where we will only do legal or critical documents. Say, if you are a university student, you may need assessment urgently and translated quickly, which would be more critical than someone wanting recipes translated. We have not reached that stage yet, we are still offering our full service.

“It is highly personal work, in an example of a job I have on my desk right now I have a phone book which needs 38 edits. Trying to contact someone interstate and writing a letter when you are blind, including each of those 38 edits would just be too hard and it is not practical.

“The government tender did not actually ask us about the work that we do. The tender did not ask about providers in SA and it did not ask about what the effect of removing our funding would be.

“Everyone approved under the tender is a national provider, but 99 per cent of our audience is local. The tender did not ask questions about how to address the gap without a local provider.

“Our more frequent users are elderly and they will find it too hard. Around 80 per cent of our clients are more than 65 years old. If they will go without they have to rely on other people, such as family or carers, people living with them to read their documents to them and that is not empowering. People need to be able to read their own licenses, bills and other documents and it is a loss of independence.

“We are calling for people to go to our website and write to their local member, we have all of the contact details for MPs there and it can all be done from that page.”

The Royal Institute for the Deaf and Blind Children has also lost its funding under the scheme in the move.

Comment below to have your say on this story.

If you have a news story or tip-off, get in touch at editorial@sprinter.com.au.

Sign up to the Sprinter newsletter