Mention the word ‘hybrid’ and most people will think of a Toyota Prius.

But hybrid is also gaining increasing significance in printing. At Drupa, a slew of new hybrid applications emerged, covering a plethora of different presses and applications.

In fact, it’s useful to begin by asking the question ‘what do we mean by hybrid printing?’ because the answer can involve a number of different interpretations.

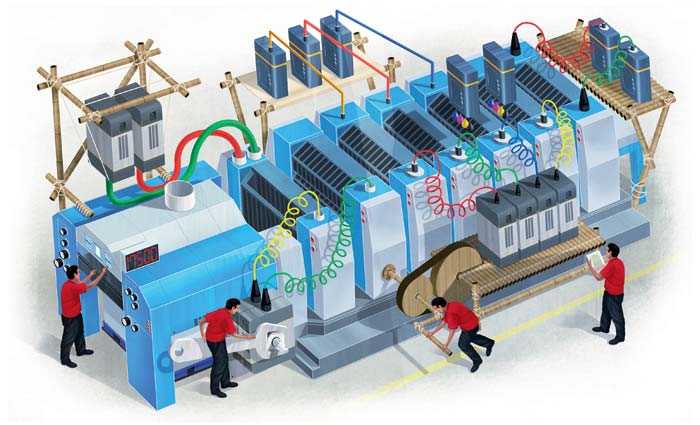

A hybrid printing system could be used as part of a sophisticated quality control mechanism, or for adding marks such as security codes. Examples of this sort of application, whereby inkjet heads are incorporated in a sheetfed press, have been developed by KBA with Atlantic Zeiser, and Heidelberg using the CodeCenter 2 system from Inkdustry.

Hybrid could also involve combining print processes by producing personalised or versioned print directly on an offset press. Some of the major installations overseas, such as Komatsu in Japan and Axel Springer in Germany, use Kodak’s Prosper inkjet heads on different presses, namely Ryobi and Manroland.

Hybrid production can also involve offline systems such as Domino with its K600i system, and HP with its new Print Module imprinting line.

An alternative interpretation of hybrid encompasses the meshing of two types of know-how, such as in the KBA RotaJet 76 inkjet web, and the Timsons T-Print digital book printing press. Here, the press manufacturers have combined their expertise in paper handling with inkjet heads from, respectively, Kyocera and Kodak. KBA’s RotaJet is producing four-colour commercial print, while the Timsons T-Print is currently black-only for book work, although Timson managing director Jeff Ward says colour is on the cards for the next phase of development.

The common denominator in all this is the way the latest inkjet printing and, crucially, drying technology, is being combined with conventional print systems in one way or another, to create something that brings significant benefits to the user.

By marrying the strengths of a clever VDP technology, usually inkjet, with the speed and quality of a host offset line, mailhouses, book printers and transactional printers – and a few other types – really can reap the best of both worlds.

Taking over from toner

The formula rapidly becoming de rigeur in this space takes an inkjet superstructure and intelligently syncs it with a web line. This is taking over from older toner-based digital printing, which offered variability for barcoding or addressing, but without the speed or quality offset can provide.

Litho is no newcomer to variable-data printing. As recently as a decade ago, long runs of offset-printed ‘shells’ were put through a laser array to achieving personalisation. This was in widespread use by the likes of Salmat. But the hassle of rehandling and two passes meant it

was far from the most productive solution.

The marriage of inkjet to other types of print handling technology is not a novel idea either. Ten years ago, this writer saw Muller Martini’s Onyx-Rubin finishing array configured with an inkjet addressing system being demonstrated in Melbourne.

The sample product was a 48pp A4 saddlestitched publication, and after it had passed through various inserting stations and a tip-on station, it journeyed under the printheads of a Tronics VideoJet inkjet printer that overprinted subscribers’ addresses to a blank field, then printed

a ‘lucky number’ in an adjacent field, before the final product was polybagged.

Early versions of hybrid printing in the direct mail world foretold of the potential opportunities by combining the versatility of inkjet with the grunt of lithographic printing. But the results were of limited use. Mono inkjet heads, generally black ink, and at a lower resolution than the rest of the offset-printed piece (mainly 240x240dpi), produced grainy, pixelated segments that stood out from their offset printed surrounds like a sore thumb. This was mirrored in a lack of enthusiasm from agencies and consumers who saw what was essentially an add-on, rather than

an exciting personalised document.

The recent breakthrough of hybrid printing is linked to the arrival of inkjet as a serious player in commercial printing. In the no-nonsense B2 format, think Fujifilm Jetpress 720, Screen Truepress Jet SX and the impending Konica Minolta KM1 and Ryobi Digital Press 8000. In the web world, mega presses for transactional or publishing include the continuous-feed HP-T series presses at Blue Star, Griffin Press and Opus, the Kodak Prosper at SOS Print & Media and the InfoPrint at Computershare.

Best of both worlds

In a sense, the uplift in hybrid printing was inevitable: hitch the economies of digital inkjet (and nowadays we’re talking high-resolution, full-colour arrays) to the lower unit costs and indisputable quality of web and sheetfed offset. You have a winning double: inkjets on steroids, if you will. Vendors caught on quickly and began offering inkjet arrays. This is essentially the same technology that powers standalone inkjet presses, but specifically designed for integration with host lines from another technology. Hybrid printing made a flashy showing at Drupa, with many new systems at the stands.

Speed is another critical factor in this kind of hybrid integration. Early inkjet superstructures acted as a considerable brake on their offset hosts. This created a productivity nightmare. But with contemporary inkjet heads rated at 2,000 feet per minute (fpm) on a 600x300dpi output, they can be run parallel to coldset, which means they are more than ready for life in offset’s fast lane. Other heads run 600x600dpi at 800-1,000fpm, a typical DM production speed.

Hybrid has leant more toward web than sheetfed, due to the applications involved. One of the few well-publicised examples of inkjet mounted on a sheetfed offset is at Japanese printing group Komatsu. The company reports a general speed of 11,000 sheets per hour in hybrid mode, 4,000 shy of the rated speed on its Ryobi press, but on balance, a worthwhile concession.

Kodak Australasia’s business services and solutions group manager, Michael Smedley, tells ProPrint that the vendor’s Stream inkjet technology meets today’s offset press speeds, as it can run at 152-900 metres per minute.

He outlines the business argument for hybrid. He doesn’t see it as a transitional model but says it will remain as a complementary approach to full inkjet printing for VDP work on any number of applications, including personalised DM and personalised forms and labels.

The latter includes a swath of different applications. Types of work will include tracking barcodes on courier forms, numbering for serialisation, multi-part forms, print numbers and barcodes on lottery tickets, barcode and security features to prevent pharmaceutical counterfeiting, lucky-winner notification on tax invoices and receipts, and unique passwords on receipts.

“The customer will increase productivity and turnaround time, decrease their workforce but not affect the types of services they currently offer, as well as printing at less cost.”

Quality inkjet

Perth printer Quality Press, based in the suburb of Welshpool, is a 17-year-old commercial printer with a staff of 70. It adopted a hybrid approach when it ventured into forms printing in 2010.

Director and co-owner Ramesh Patel says the configuration of inkjet heads to its offset line is the best of both worlds. The company integrated Kodak’s S5 mono inkjets into a five-colour Miyakoshi continuous-feed offset line for VDP numbering, barcoding and addressing.

Patel says printing these jobs in inkjet would involve click-charges as an on-cost, whereas the five-colour Miyakoshi provides a far lower unit cost per page on its A4 forms, as well as quality and speed. “It’s normal printing with variable data, and no additional costs.”

He says the two arrays of Kodak S5 inkjets have no trouble keeping up with the Miyakoshi at over 150 metres per minute. Quality Press would operate at the same throughput even without inkjet added on.

Magazine publishing is a hotbed of hybrid. European print companies have embraced the formula with gusto. German publication major Axel Springer announced in December it will introduce hybrid printing, using Kodak Prosper inkjet heads, to all its German printing sites and contract printers, entailing a multimillion euro commitment.

At the core of its investment is the ability to run a strip of monochrome variable data at full press speed for special competitions and promotions in flagship newspaper title Bild. By May, when the installations will have been completed, Axel Springer will be using no fewer than 30 Prosper printheads on a range of host web lines, including its Manroland Colormans and its KBAs.

Kodak says it has reached considerable global traction with its inkjet heads. Not counting sales of its full-blown Prosper inkjet web presses that incorporate those heads, around 500 standalone Prosper heads have been installed worldwide.

Full inkjet or hybrid?

Hybrid printing has also made inroads in Britain, with CN Newsprint installing the world’s first Prosper S10 system and News International running tests.

US direct mail colossus Consolidated Graphics (CGX) was an early adopter of hybrid printing, using 240dpi heads for the past eight years. In 2011, it advanced to Prosper 600dpi versions, with a Kodak S20 Imprinting System, to handle its short-turnaround, personalised brochure work on volumes in the millions.

At CGX, part of the success story hinges on the ability to move heads to different presses and different components of the finishing process, depending where the big throughput will be that day. As many as 16 inkjets — the width of two B1 sheets – have been used. Presses are set

up for a job with multiple heads front and back. After printing and drying on the web, the work goes through a series of turnbars to a racking system where the Kodak S20 heads add the inkjet component. These can include geocode mapping, barcodes, personalised URLs, geotrackable coupons and micro-promotions for stores based on the recipient’s location. The piece is then slitted and folded. It’s zippy work – and leaves the old sheetfed alternative sputtering at the start line.

CGX is also a customer for Kodak’s standalone Prosper presses. In November 2011, it added a Prosper 5000XL to one of its key facilities in New York state for digital colour work. But CGX is clearly an ideal player for hybrid imprint technology, characterised by its triple requirement of extreme speed to market, variable-data components and quality output.

Hybrid printing is at somewhat of a sweet spot, says Presstek’s Asia-Pacific director, Tim Sawyer. He points out that toner’s weak spot is its cost on longer runs, while the weakness for standalone production inkjet is its cost on shorter runs. That is what makes hybrid inkjet-offset a prime option.

While much of the buzz is around web-hosted lines, there is also integration with sheetfed. Atlantic Zeiser has developed an inkjet system for KBA presses, while Inkdustry’s Codecenter technology is available for Heidelberg lines.

Some hybrid configurations are more complex than inkjet heads on offset presses. Take the KBA RotaJet inkjet web and the Timson’s T-Print book press. Both are inkjet, with the RotaJet using Kyocera colour arrays and the T-Print using monochromatic heads from Kodak.

Meanwhile, HP’s new imprinting inkjet modules, rated at 244 metres per minute, which had their debut at Drupa, have thrown down a challenge to Kodak, which leads the market with its Prosper heads. HP’s Print Module Solutions inkjet heads configure with Domino’s K600i system, which is available locally through Insignia Australia. But HP is not offering any hybrid printing solutions in the South Pacific region at present, a company spokesperson told ProPrint.

Presstek promotes its 75DI direct-imaging press, launched at Ipex 2010, as a contender in the hybrid imprinting stakes. As one of the few machines on the market using DI technology, the 75DI is already somewhat of a hybrid press. At Drupa, Presstek was talking up the possibility of integrating the press with Kodak S5 inkjet heads, adding the option for VDP and creating some kind of chimera machine.

DI’s strength is its ability to keep unit costs in offset territory, but without the downside of offline platemaking. Add to that features such as coating, printing in 10 colours and inline convertible perfecting, says Presstek’s Sawyer. “Especially with the 75DI, the ability to add variable data to all of its other capabilities is a competitive advantage and a feature that is drawing a significant amount of interest from the market.”

Sawyer says the 75DI slows from its rated 16,000sph to 10,000sph when fitted with inkjets, and the company is working with its OEM partners to narrow that gap. “However, even with the press slowing down, the elimination of a separate offline inkjetting step and the elimination of the need to produce longer runs of variable data on toner-based digital devices justify the application from a pure time and cost perspective, increasingly critical in a just-in-time environment where costs and cycle times are always under pressure.”

Mixed feelings: hybrid for publishing

With its reverse takeover of McPhersons midway through last year, the Opus Group has arrayed a versatile mix of book printing technologies across the Maryborough, Victoria facility and its Ligare Printing site in Riverwood, NSW.

So hybridising digital and analogue printing of books is a prospect Opus has considered. It hasn’t dwelled on this too heavily at this stage, reflects Richard Celarc, general manager of publications.

The group has also weighed the option of converting some web lines to inkjet, but it’s early days and Celarc is waiting to be convinced by “a practical and a commercial solution”.

Alongside its sheetfed presses, Ligare runs three Veriquick web offset lines, while McPhersons runs four Timson web offset presses and two Hantschos. Before the McPhersons merger, Opus considered converting its Veriquicks into inkjet, says Celarc. But the cost of $1.5-2 million to beta-convert a Veriquick, which carried an original price tag of around $3 million, was unfavourable. It would have to come down considerably to make it a better proposition than buying a new inkjet book press.

Bringing McPhersons into the Opus stable with its HP T400 inkjet web press, part of its Onyx book line has pre-empted the need to buy in additional inkjet muscle.

“The speed, quality and cost of inkjet is making it more and more reasonable to work with inkjet than with offset,” Celarc says. He notes that inventory-shy book publishers are now more likely to order 50 runs of 1,000 than one run of 50,000.

Celarc also notes that Timson offers a digital book press, the T-Print, which it R&D’d from its Timson offset book press.

Comment below to have your say on this story.

If you have a news story or tip-off, get in touch at editorial@sprinter.com.au.

Sign up to the Sprinter newsletter