Almost everyone under the age of 35 has spent a large part of their life in front of a screen. It could be a TV, computer monitor or mobile phone. There is a screen at the petrol pump and the ATM machine. In three decades, we have gone from a society based on paper to one based on pixels. With books on the iPad, bills online, newspapers and magazines on the web, RSS feeds, tweets, Facebook photos and YouTube videos, more than 90% of our reading is done on a screen.

Reading itself has changed. In the Journal of Research in Reading, Norwegian researcher Anne Mangen wrote that screen reading and page reading are radically different. “The feeling of literally being in touch with the text is lost when your actions – clicking with the mouse, pointing on touch screens, or scrolling with keys on touch pads – take place at a distance from the digital text, which is, somehow, somewhere inside the computer, e-book or mobile phone.” She concluded: “Materiality matters… One main effect of the intangibility of the digital text is that of making us read in a shallower, less focused way.”

In 2008, media critic William Powers wrote an essay in defence of paper called Hamlet’s BlackBerry: Why Paper Is Eternal. He said: “There are cognitive, cultural, and social dimensions to the human-paper dynamic that come into play every time any kind of paper, from a tiny Post-It note to a groaning Sunday newspaper, is used to convey, retrieve, or store information.”

Paper will never die, said Powers. “It becomes a still point, an anchor for the consciousness. It’s a trick the digital medium hasn’t mastered – not yet.”

Younger people don’t mind using screens. Christine Rosen said it best in The New Atlantis: “The book is modernity’s quintessential technology – a means of transportation through the space of experience, at the speed of a turning page. But now that the rustle of the book’s pages competes with the screen’s blinking pixel, we must consider the possibility that the paper book is endangered. If we choose to replace the book, what will become of reading and the print culture it fostered?”

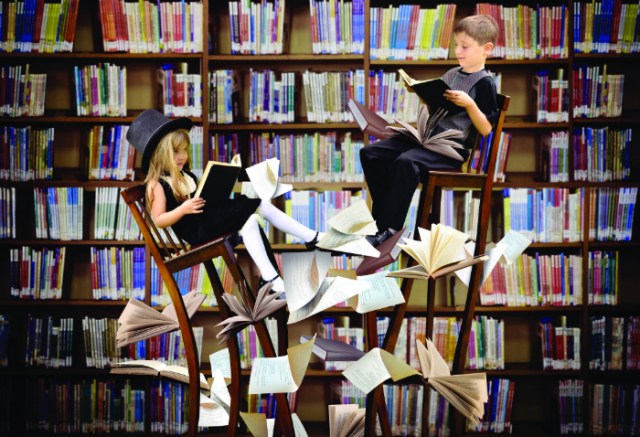

In 2007, the US National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) published a report: To Read or Not To Read: A Question of National Consequence. It provided ample evidence of the decline of reading for pleasure, particularly among the young. Nearly half of Americans ages 18 to 24 read no books for pleasure; ages 15 to 24 spend just seven to 10 minutes per day reading voluntarily; and two-thirds of college freshmen read for pleasure less than an hour per week or not at all. The real difference isn’t between households with computers and without them; it is the one between households where parents teach their children the old-fashioned skill of reading and instil in them a love of books and households where parents do not do this.

Doctors and researchers note that paper can offer more visual sophistication than a screen. But certain types of paper, including inexpensive newsprint and the paper in softcover books, can actually provide a reading experience inferior to electronic alternatives.

There are numerous display technologies available, from B&W e-ink technology found in Amazon.com’s Kindle and the Barnes & Noble Nook to the full-colour LCD display of Apple’s iPad. Does one technology offer a better reading experience than the others? And are these technologies better than paper?

Different screens make sense for different uses. It depends on the viewing circumstances, including the software and typography on the screen. E-ink is great in sunlight, but in certain situations a piece of paper is a better display in dim light, and an LCD display can be better than all of these technologies. The trend appears to be moving from paper versus screens to screens versus other screens.

Frank Romano is professor emeritus at the Rochester Institute of Technology

Comment below to have your say on this story.

If you have a news story or tip-off, get in touch at editorial@sprinter.com.au.

Sign up to the Sprinter newsletter